Fesenko Kirill, Sukhorukov Konstantin. Russian state and national bibliography: challenges of today and opportunities of tomorrow. Panel presentation at ASEEES 2022 conference

|

| Hello, my name is Kirill Fesenko. I would like to thank Joe Lenkart and Katherine Ashcraft for inviting me to speak at this panel. Also, I would like to thank Konstantin Sukhorukov, a chief editor of Bibliographiia journal and one of top experts in the field of Russian National Bibliography, who kindly provided me with invaluable insights and useful information for this presentation. |

|

|

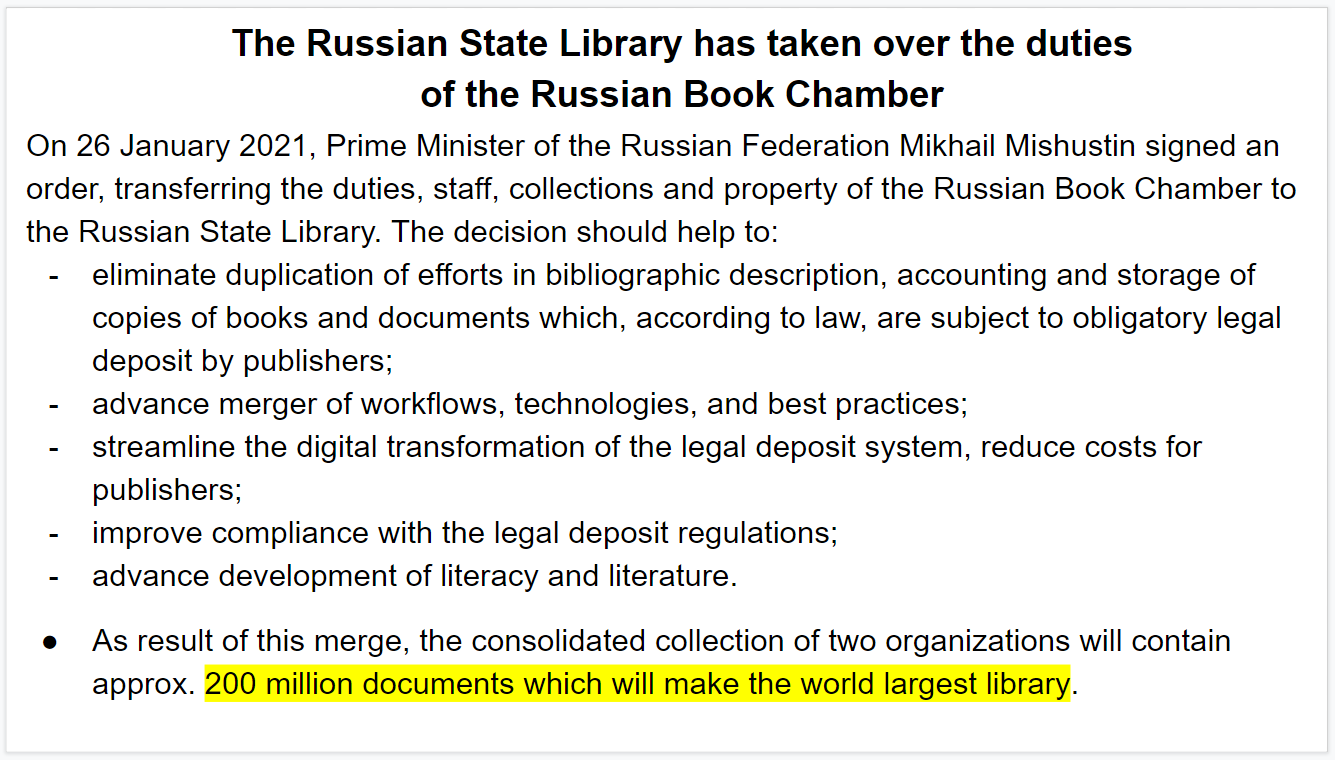

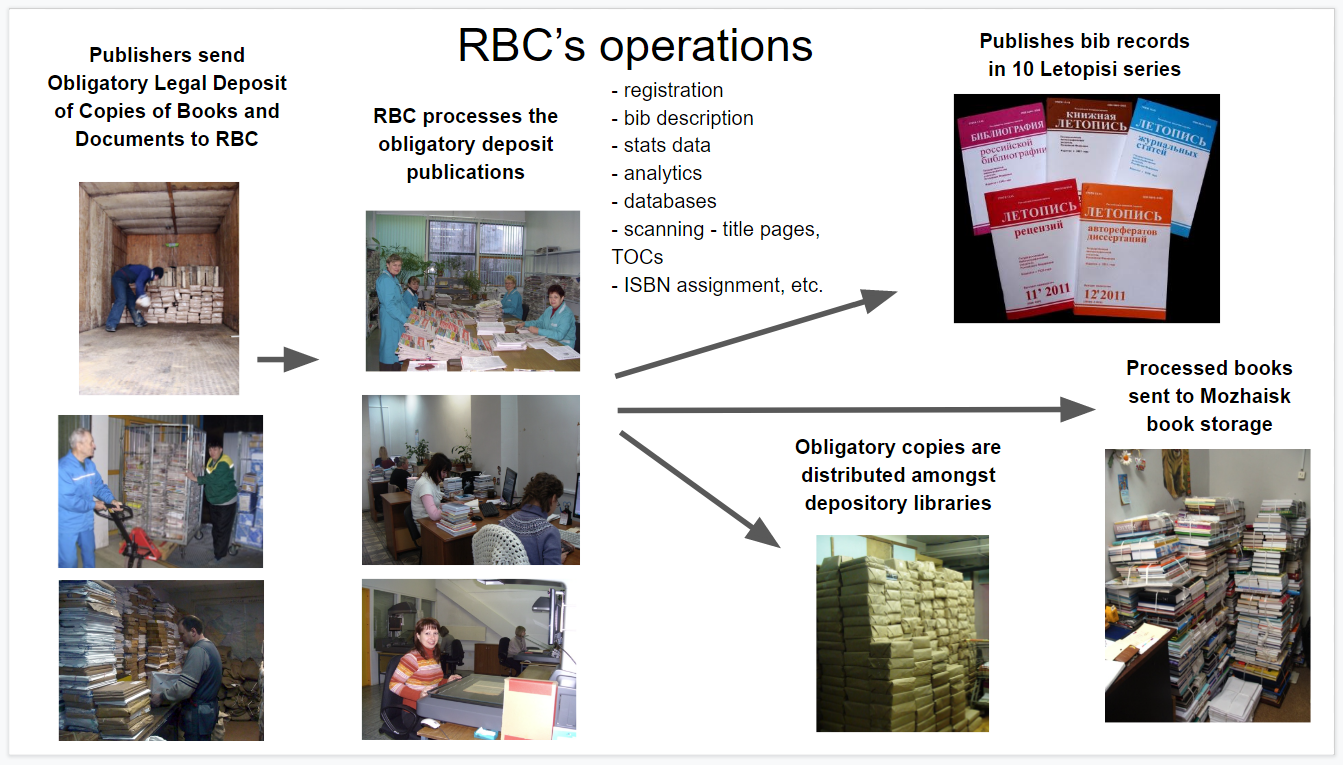

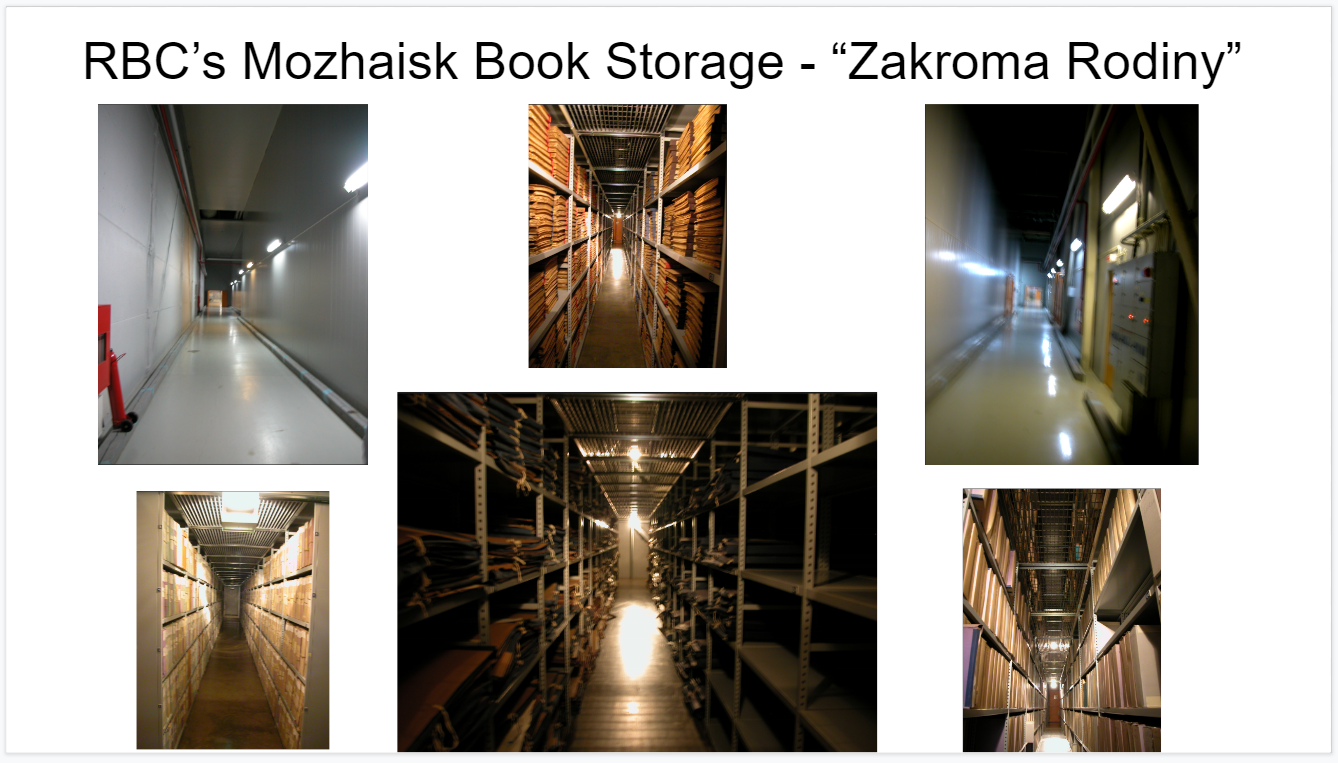

Until last month, Konstantin also held a second position – a deputy director for research of the Russian Book Chamber, the country’s national bibliographic agency. The Book Chamber, after about a year and a half long transition period, formally ceased its existence as an independent organization earlier this fall by merging with the Russian State Library, formerly known as The Lenin library. This is a truly big change in the whole field of the Russian state and national bibliography. The State Library has been presenting this merge in the media as one which creates a collection of 200 million documents which makes it now the world’s largest library. There are some questions about this number but, for now, we’ll leave it for another discussion. Time will tell what will come out of this merge. The elimination of duplication of bibliographic description efforts is mentioned as one obvious benefit. Both organizations have been routinely processing and describing the same obligatory deposit material. Another plus is the economy of “one window” for legal deposit which the publishers can use now instead of two. The merger also stimulated discussions to create new large unified online bibliographic databases such as the National Bibliographic Resource and the Union National Book Platform. Among the possible drawbacks of the merge in the longer term may be the decrease in the number of titles publishers send in to comply with the obligatory deposit law. Over the many decades, the Book Chamber established a special level of trust with the publishers who were rest assured that their obligatory copies were used for the bibliographic registration only and then sent to the “eternal storage” in the RBC’s massive Mozhaisk facility. The State Library, on the other hand, is known to digitize and use newly received obligatory deposit copies of commercial publications for various purposes without publishers’ consent, including in the National Electronic Library. The Book Chamber is also focused on providing special services to the publishing community at large including book publishing and market research as well as development of new standards for publishing and book trading industries. There is a concern that under the State Library’s control, the national bibliography operations will get gradually slanted more towards service to the library community instead, and these Book Chamber functions will die off in time. This worries the Russian book publishing and trading communities which are relying on these services from the Book Chamber. |

|

|

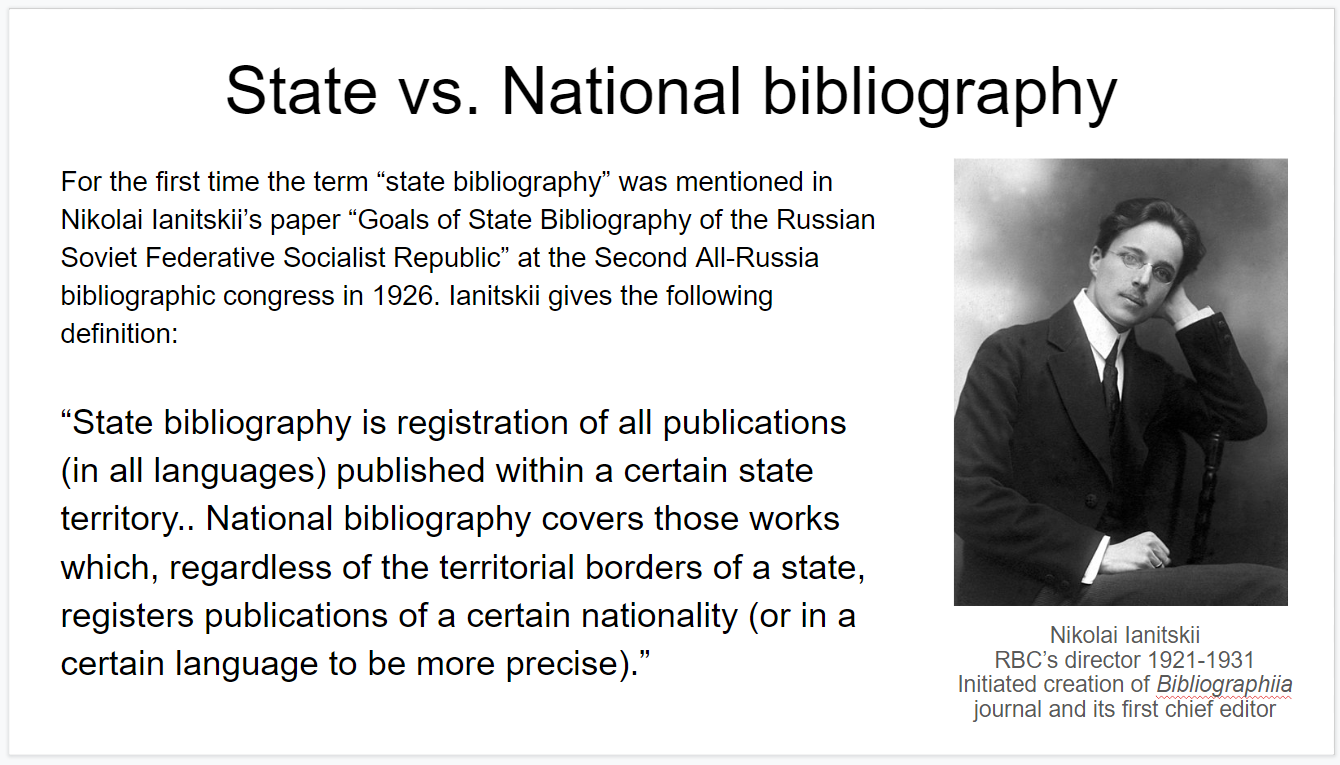

Finally, Konstantin Sukhorukov believes that with this change we are witnessing possibly the final stages of the downfall of what was left from the Soviet Union’s state bibliography infrastructure which served as a base for all types of bibliographic publications, providing the country and international community with the most authoritative and complete retrospective, current and prospective bibliographic information. For the most part, it became possible due to a finely tuned state system of “Obligatory Legal Deposit of Copies of Books and Documents“ which publishers and publishing organizations have to hand over to the RBC. This system was also closely interlinked with the censorship in the USSR. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, many foreign terms replaced traditional Soviet ones in various spheres of book business, including bibliography. Sometimes it was caused by real needs because the societal change affected not just the general principles, but also the practical methods and structural components of almost all branches of the book business. But at other times introduction of new terms was caused by fashion and certain traditional Russian glorification of everything foreign. This way, for example, the standard Russian language term “оформление книги” is now commonly referred to as “бук-дизайн”. Finally, this change was also driven by a desire to establish a new ideological model of culture (including in the field of bibliography) only because the former model was viewed as having a Soviet stigma imprint on it. All of this contributed to the gradual replacement of the term “state bibliography” by a new term “national bibliography” as it relates to the contemporary theory and practice of bibliographic registration in the scale of the whole country. The Book Chamber’s merger with the State Library will further contribute to the downfall of the old Soviet state bibliography paradigm in favor of the national bibliography one. Due to the lack of time, I need to wrap up this “state vs. national bibliography” topic now, unfortunately, as there is more interesting info on this from Konstantin. I just want to add that thanks to Konstantin I also found out that Nikolai Ianitskii, RBC’s director in the 1920s, besides laying the foundation for the system of state bibliography, also greatly contributed to the creation of local Book Chambers in the union and autonomous republics of the USSR, and he also initiated registration of publications in many languages of USSR peoples and addition of these bib records to Knizhnaia letopis. Among his other achievements is improvement of the publishing statistics, organization of international book exchange, development of connections between the Soviet and foreign book publishing and library-bibliographic organizations. I thought it is appropriate to mention this in the context of your panel. Perhaps, this Nikolai Ianitskii heritage is worth a separate discussion some day. |

|

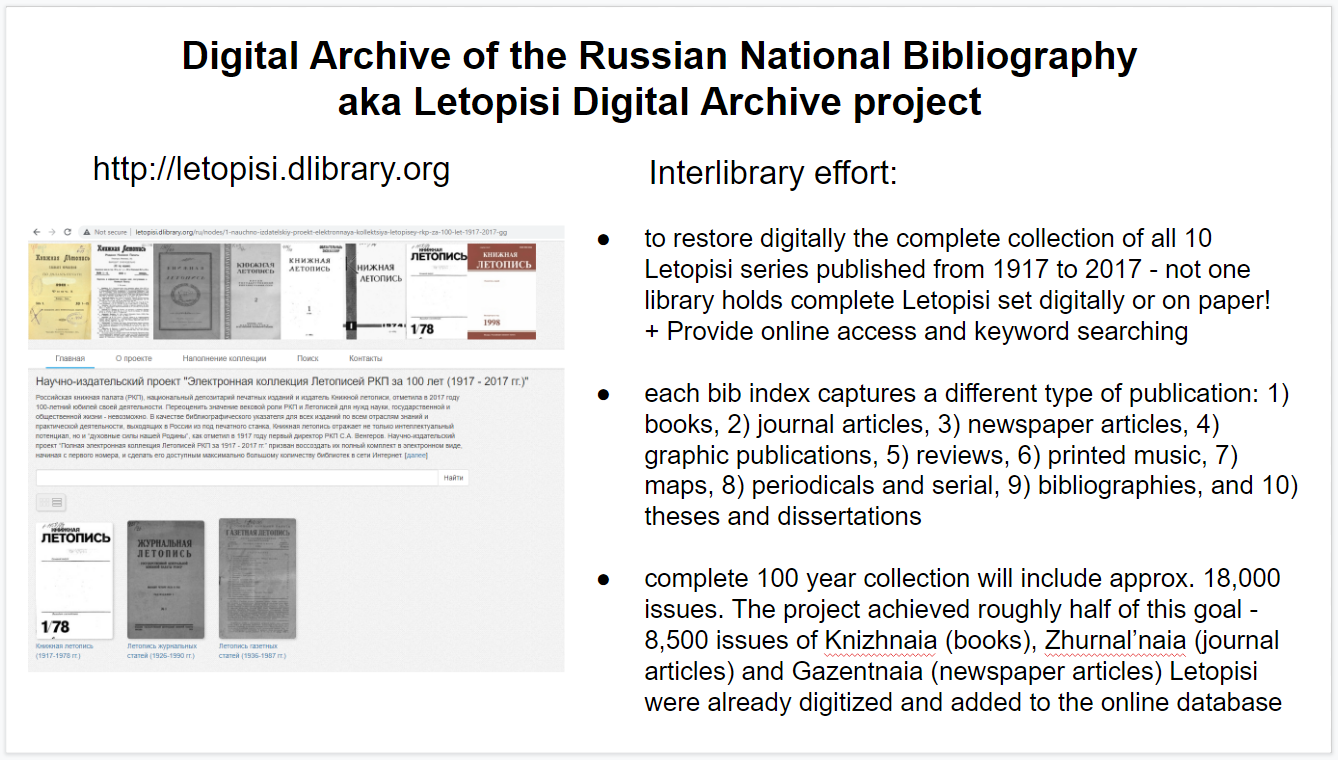

| But let's move on - the second half of my presentation will get a bit more interesting visually. Here I am getting closer to the Letopisi Digital Archive Project but first I would like to show how the Letopisi titles are produced by the Book Chamber and to provide you with some statistics on Letopisi coverage of the country’s publishing output.. |

|

|

|

|

I talked with the researcher who reported that the Letopisi Digital Archive "changed her understanding of published literature during the Stalin era" to find out more details about this experience. The researcher said that before getting access to the Archive she majorly based her research on reputable and highly referenced articles and publications on the subject of published literature during the Stalin era. Letopisi Digital Archive allowed the researcher to browse the long lists of titles, check their print runs and to see nuances of their subject groupings in Knizhnaia letopis’ for that period. Such browsing helped the researcher to develop a new understanding and much better picture of the societal attitudes and major themes for the period. The researcher was surprised to realize that much more foreign literature was published during the Stalin era compared to what the research articles on that subject showed, that many more new authors appeared in 1943 compared to 1937, and so on. I think this sounds like an example of a certain “echo chamber” created by the mainstream research articles on the subject which the Letopisi Digital Archive helped the researcher to break through and extract a new different understanding of her subject matter. This is why, I think, as students and scholars face a growing "information clutter" and similar cases of “source echo chambers”, including on the internet, the role of national bibliography as a wide net for higher quality information and resources increase. I think there are outstanding opportunities in this area, including some that were mentioned in this presentation, and plenty of room for collaboration too. As an information researcher, besides improving scholarly access to the large historical spans covered by the national bibliography records such as Letopisi titles, I am also curious to see if there will be any interesting opportunities to dig deeper into “the dark matter of the USSR/Russia information universe” or those 10-40% of publications which avoided capture by the USSR/Russian state bibliographic system and Letopisi record, as I mentioned earlier. But even in terms of the works that were captured in Letopisi, I am finding some interesting cases of ghost works which are not findable on the Internet and in the online catalogs of Russia’s largest national libraries. My rough estimate is that such ghost works represent very roughly 2-3% of Knizhnaia letopisi records, but I suspect that the number of ghost works will be much higher in Letopisi zhurnalnykh and Letopisi gazetnykh statei. I think these are potentially interesting topics for research. |

|

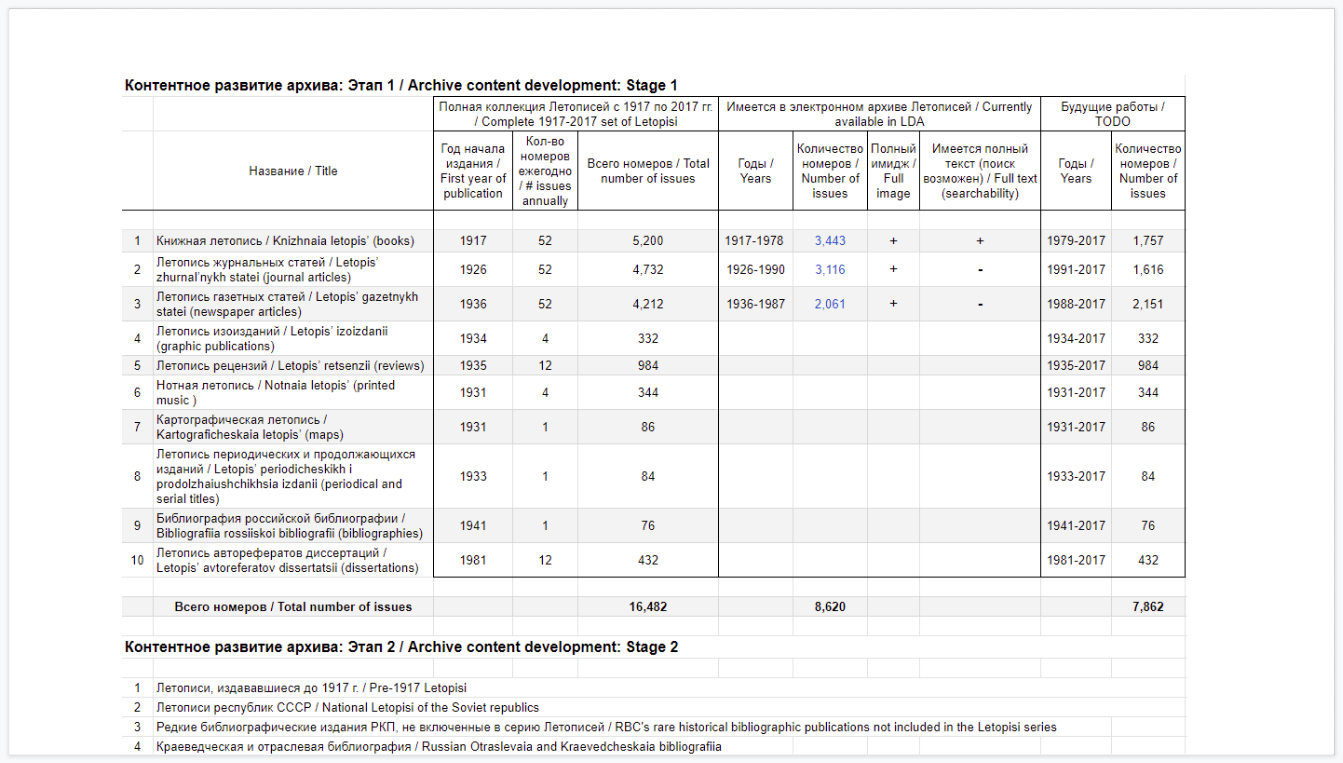

| Letopisi Digital Archive content development plans |

|

|

|

|

|